The U.S. Army Air Force C-47 transport approached a dirt airstrip in North China, an informal ground crew guiding it in for landing while bystanders watched on a late July day in 1944. As the plane’s wheels touched down, all initially seemed well—until a loud boom sounded, the aircraft veering sharply to its left and coming to a stop. The passengers on board hastened to exit the plane, which had suffered damage to its landing gear and a propeller when one wheel fell into the depression created by an old grave inconveniently located along the landing strip. A stunned welcoming party of Chinese Communists watched ten Americans scramble to assemble themselves once on the ground. The group’s leader, U.S. Army Colonel David B. Barrett eventually gathered his composure and declared, “We are mighty glad to be here, at last.”

This incident marked the launch of the U.S. Army Observer Group in Yan’an, more familiarly known as the Dixie Mission (because the Chinese Communist Party, the CCP, held “rebel” territory). “Under other circumstances,” historian Sara B. Castro writes, “landing with one wheel stuck in a grave might have appeared inauspicious—a bad omen for the start of a diplomatic relationship.” Amid the upheaval of war and a messy tangle of domestic politics in China, however, both sides quickly recovered from the incident. “Recognizing obstacles and then shaking them off to move forward became a recurring theme of relations between this first group of American observers and their CCP hosts,” Castro explains.

The 1944-1947 Dixie Mission is the centerpiece of Castro’s 2024 book, Mission to Mao: US Intelligence and the Chinese Communists in World War II. Castro is not the first to tell the story of the Dixie Mission, she acknowledges, but she’s specifically interested in the people who served on this mission and how their work played a part in the growth of America’s intelligence regime. Castro approaches the study of intelligence history with the tools of social and cultural history, putting high-level political debates in the background and focusing instead on everyday interactions on the ground in Yan’an. “Mission to Mao,” she writes, “is a social history of US intelligence focused on the role of human relationships, social networks, factions, rivalries, and personalities involved in the Dixie Mission—a roots-up, everyday perspective on events.”

There were personalities aplenty surrounding the Dixie Mission, starting at the top with “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, head of U.S. forces in the China-Burma-India theater during World War II. Stilwell clashed early and often with Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, who had been battling the CCP for control of China until war intervened in 1937 to refocus their attention on fighting the Japanese. As part of Chiang’s grudging agreement to work with Stilwell, he forbade the Americans from making contact with the CCP base in Yan’an. Up to 1943 Stilwell abided by these terms, but eventually the acrimony in his relationship with Chiang led Stilwell to seek other allies in fighting the Japanese. Enter the idea for a mission to Yan’an.

Protracted negotiations with Chiang ensued, which lasted until U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace made a visit to China and personally persuaded Chiang to approve what became the Dixie Mission. Colonel Barrett, an old China hand and colleague of Stilwell’s, was tapped to lead a dream team of China experts from five different agencies. As Castro writes, “The initial roster of participants in the Dixie Mission boasted the most expertise on Chinese language, culture, politics, and history” of any American group that would serve during the mission’s three-year lifespan. Hopes were high as the Dixie Mission began, its members undaunted by that bumpy landing in Yan’an.

The two sides got off to a strong start. CCP leaders Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De, and Ye Jianying were all available to meet regularly with their American guests and seemed to delight in hosting them for meals. Both parties shared what they knew about Japanese fighting capabilities. Dixie Mission staffers set up weather information collection equipment; rescued, assisted, and debriefed downed Allied airmen; and established radio capabilities to collect intelligence. The Americans were eager to gather information, and the CCP, hoping to cultivate them as allies, welcomed them to the base.

This productive honeymoon period of the Dixie Mission lasted only a few months. Despite the congenial working relationship between two sides, the Americans weren’t fully prepared for how the mission would raise CCP expectations of U.S. support in the Communist fight against Chiang and the Nationalists. The Americans hoped to negotiate a working collaboration between the ideological opponents, not support one over the other, and this mismatch in priorities would lead to disappointment. Mission members also soon realized that the interagency nature of the project meant that “the arrangement left room for redundancy of efforts and occasional friction,” and that the “broad and ambiguous goals” of the endeavor provided little direction for the group’s participants. As summer faded and cold weather swept across the North China plateau, it seemed to push away the optimism of those early days.

In October 1944, Franklin Roosevelt recalled Stilwell after the latter engaged in a showdown with Chiang Kai-shek, depriving the mission of a key supporter. The situation took a turn for the worse the following month when General Patrick Hurley arrived in Yan’an as a special envoy from Roosevelt. Hurley knew nothing of China and charged into the situation thinking that he could fix things between the CCP and Nationalists. Instead, he quickly made a complete hash of his assignment, to the exasperation of the China experts who understood that the gulf between Mao and Chiang wouldn’t be easily bridged. (Hurley’s choice to greet Mao and Zhou with “a full Choctaw war whoop” when he landed in Yan’an probably didn’t win him any points, either.) By the end of 1944, the energy and optimism of the Dixie Mission’s first weeks had fully fizzled.

Yet the mission limped along throughout the remaining months of the war, a small group of Americans in Yan’an doing what they could to collect intelligence, write it up, and submit their reports to various agencies in Washington. Hurley, now the ambassador to China, continued to wreak havoc, blocking any suggestions that the United States provide assistance to the CCP over the Nationalists. By the time Roosevelt died in April 1945, the Dixie Mission had been so gutted and demoralized that its members focused on weather and radio systems, rather than acquiring the kind of on-the-ground knowledge of the CCP that might have served the U.S. well in its future analysis of the situation in China. In August 1945 the war with Japan ended; almost immediately, Mao and Chiang resumed their fight for control of China, the United States backing Chiang despite the reservations expressed by many seasoned China experts.

A skeleton crew of U.S. staffers stayed on in Yan’an until 1947, but for all intents and purposes the Dixie Mission had a productive lifespan of only a few months. Despite is brief heyday, the mission remains more than a footnote in the history of U.S.-China relations. It was, Castro informs readers, “the first sustained official engagement between US government officials and the CCP,” and could have yielded far deeper understanding of the Communist cause if intelligence officials had been able to work without interference from above.

The Dixie Mission also played a role in the reorganization of the American intelligence regime during and after World War II. If you’ve ever wondered why the CIA (founded in 1947) is the “Central” Intelligence Agency, then Mission to Mao offers detailed insight into the need for such an organization. Castro effectively conveys the fragmented, territorial, and deeply personalized nature of wartime intelligence operation; it was a wonder anything got done, given the delays, inertia, bottlenecks, and gatekeeping that plagued the field. “Inefficiency and unprofessionalism within the US intelligence process,” Castro argues, were equally or even more important than anti-communism in determining what information made it back to Washington, D.C. and onto the desks of key decision-makers. “The Dixie Mission case,” Castro writes, “clarifies that simply placing capable experts in the field to collect information is not nearly sufficient to achieve the goal of arming policymakers with the information they require.” This is a lesson equally important to heed today, as Donald Trump’s destructive, chaotic, and highly personalized approach to the presidency has resulted in the dismantling of the very institutionalization created in the years following World War II.

Despite that inauspicious first landing in Yan’an, the Dixie Mission wasn’t doomed from the start. Its initial members included China experts who were genuinely interested in engaging with the CCP and learning about operations at their base. But as Castro argues, a mix of strong personalities, logistical obstacles, and insufficient institutionalization combined to hinder their work. Maybe the United States was never going to back Mao and the CCP over Chiang and the Nationalists, but the American government had the chance to know a lot more about the Communists than they did. This missed opportunity makes the Dixie Mission a “what if?” moment in U.S.-China relations—one that’s important to remember when looking at the decades of Cold War chill that followed.

As a bookshop.org affiliate, I earn a small commission if you use the above link to purchase this book.

Review copy provided by Georgetown University Press.

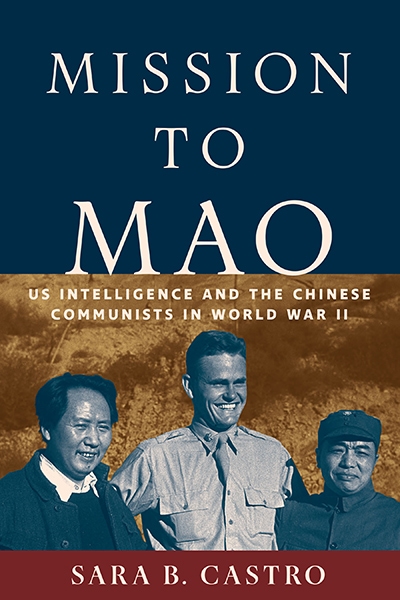

Featured photo: Dixie Mission commander Colonel David D. Barrett (right) and Mao Zedong (middle) in Yan’an, 1944. Photo via Wikimedia Commons, in public domain.

Leave a comment