Shifting, looping white lines scrolled across a black background, moving in seemingly random directions, on the video screen in front of me. Rhythmic electronic music played through the headphones I wore. The combination of visuals and music had me in a trance. Only an awareness of the other exhibition-goers who waited for their turn in front of the artwork prompted me to remove the headphones and step aside.

Mesmerizing, I wrote in my notebook. Fluidity. Repetition. Patterns.

These words followed me through two circuits of Infinite Images: The Art of Algorithms at the Toledo Museum of Art on a recent Friday. A special exhibit (on view through November 30) focusing on digital art, Infinite Images highlights the work of those who use mathematical approaches, as well as new tools like blockchain and artificial intelligence, to create generative art.

The earliest pieces in Infinite Images are by Conceptual artists of the mid-20th century, with emphasis on Hungarian-French computer art pioneer Vera Molnár (1924-2023). Molnár’s long career meant that she worked through numerous generations of technology, starting with plotter machines in the 1960s and ’70s to the graphical displays of the 1980s to her final piece, created on the blockchain shortly before her death at the age of 99. Looking at a print from Molnár’s Des(Ordres) series—intricate groupings of concentric squares, printed on long strips of dot-matrix computer paper—I remembered the Logo programming classes my elementary school taught, the instructor walking us through one command after another to draw simple shapes on the screen. Generating a circle felt like the pinnacle of achievement, and I can only imagine how long it took Molnár to produce a single one of her pieces back in those days.

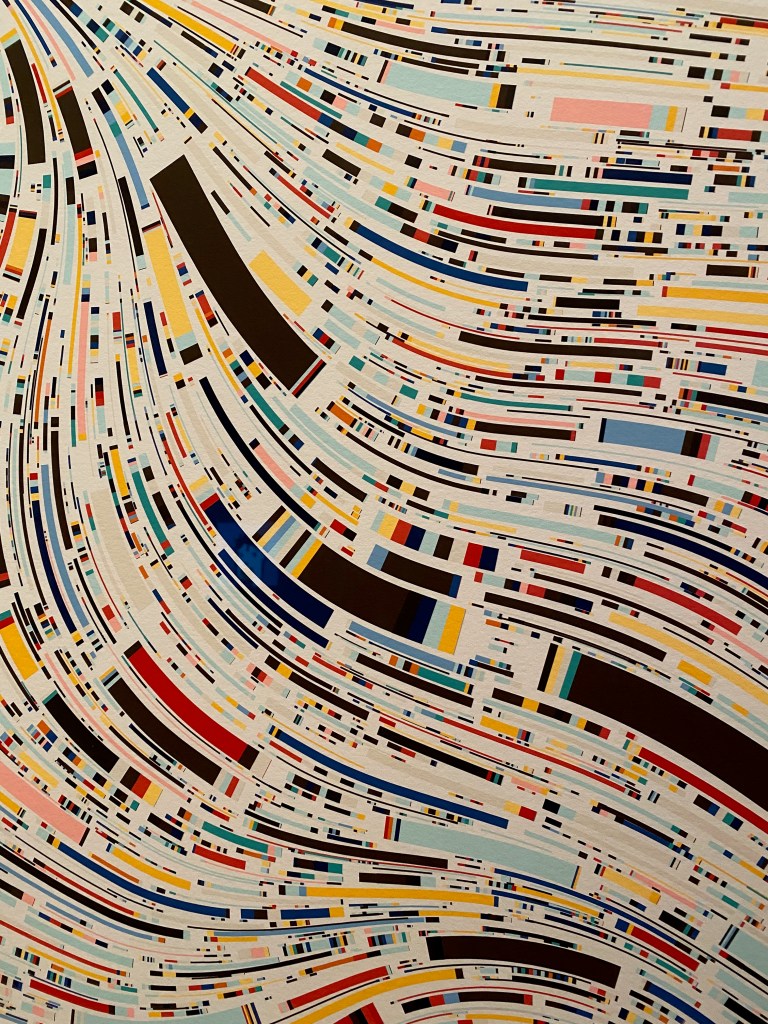

This point became especially notable as I moved into the next section of Infinite Images and quickly realized that many of the explanatory placards noted that the artworks on view were among hundreds, often thousands, produced in each series. Working with computers far more advanced than those initially available to Molnár means that contemporary artists can create algorithms that result in outputs on a large scale, whether printed as a physical art object or appearing as pixels on a screen. A dozen rectangular displays, for example, showed the ever-changing colorful slinky worms of Chromie Squiggles, “a vibrant, playful series of 10,000 unique works that depict a flowing line of color gradients.” Artist Erick Calderon (Snowfro) built the algorithm underlying the piece but neither he nor the viewer knows what the next squiggle will look like. This, like many of the works in Infinite Images, involves an element of releasing artistic control and letting the computer program determine how the piece will unfold. A quote by Casey REAS printed in large font on one wall reinforced that some generative artists create recipes rather than finished works:

Because it’s a set of instructions, the Work is essentially immaterial, but it’s always realized as light and/or sound. In fact, the instructions exist only to choreograph images and sounds in time and space.

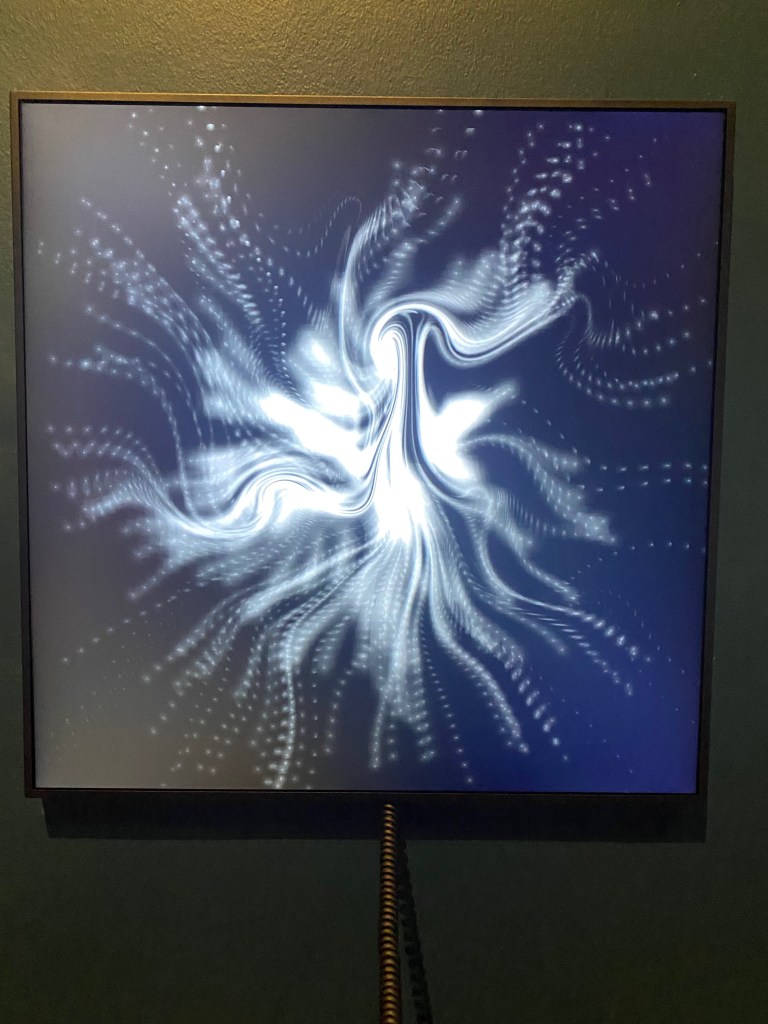

I found myself considering this duality as I walked around. The computer programming required to create such works requires order and precision; the resulting artworks emerge in ways that play on chance and randomness. Images can be unstable, ephemeral. The ever-changing screens of Color Blinds Study #4, by Zach Lieberman, and Jardins d’Été, by Quayola, for example, encourage visitors to linger in Infinite Images, as they should be viewed for extended periods so the audience can see how they transform over time.

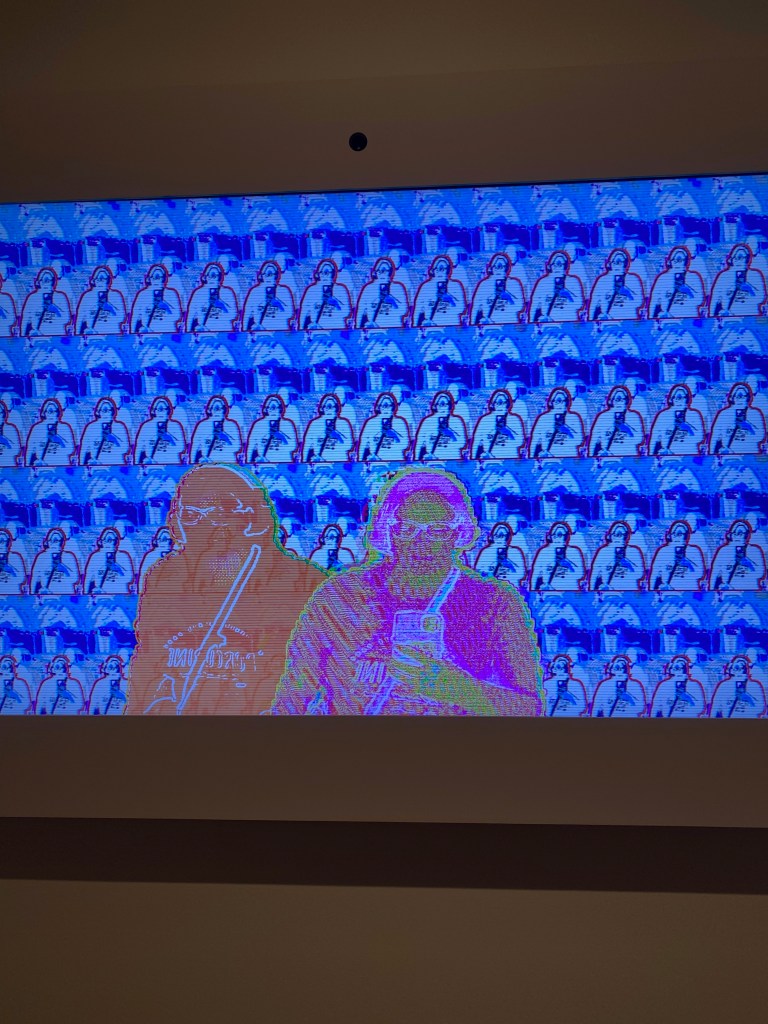

Some pieces are also interactive, enabling audience members to engage with the artwork in a more direct manner. The one I enjoyed the most was Self Emergent, designed by Emily Xie, which consists of a camera that captures the figure(s) before it and feeds this image into an algorithm that then turns the viewer into a colorful moving digital image reminiscent of the early MTV aesthetic. I’m so accustomed to thinking of such cameras and algorithms as tools of surveillance that it took me a minute to shake that perspective off and approach Self Emergent in the spirit of having fun. (Though I still wondered: is Xie recording the people who approach the artwork? What happens to these images?)

The final section of Infinite Images spotlights generative artists who find inspiration in nature for their work. Here, I was most interested in the pieces that look like they could be real but aren’t, created by artists who feed large quantities of images into programs that generate composites—flowers, for example, that seem like they should exist but don’t. Pieces like Earthly Delights 3.2 by REAS and Sediment Nodes #1 by Entangled Others (Feileacan McCormick and Sofia Crespo) reminded me of work by Chinese artist Xu Bing. In A Book from the Sky and other installations, Xu has created images that share all the elements of Chinese characters but are simply nonsense words. Such pieces are both playful and provocative: if something appears to have all the characteristics of its category, would you be able to identify it as fake?

I left the overheated special exhibition gallery and walked down the museum’s main corridor somewhat aimlessly, searching only for a bench where I could cool off and finish writing up my notes. I wound up in the atrium devoted to classical art, cool with marble and practically monochromatic after the visual stimulation of Infinite Images. I looked up from my notebook and took in the statues around me, solid and unmoving. Will the pieces in Infinite Images be as durable? I jotted down, a question that plagues the digital age. We are creating more than ever before—but what will happen to it all?

Maybe this is the question of a historian, a pack rat who saves birthday cards and ticket stubs in the archive of her life. I have little problem letting go of assumptions about “the perceived superiority of the physical art object”—one of the goals of Infinite Images, as the exhibit introduction text states. The challenge, for me, is imagining how pieces will survive, technologically, for future generations to experience them.

Perhaps I’m still more attached to the physical art object than I’d like to admit. If an artist can relinquish control over the output of their work, can they also let go of the idea of permanence? Are these pieces even meant to be permanent? How can we ensure that future generations will share the feeling of standing in front of an artwork in motion, entranced by its combination of flowing lines and pulsing music? I left the exhibit invigorated by much of what I had seen but also wondering what the early 21st century galleries of future museums might look like. Infinite Images demonstrates the possibilities of generative artwork while also raising questions about the long-term limitations of this genre.

Featured image: Infinite Petals, by Sarah Meyohas

Leave a comment