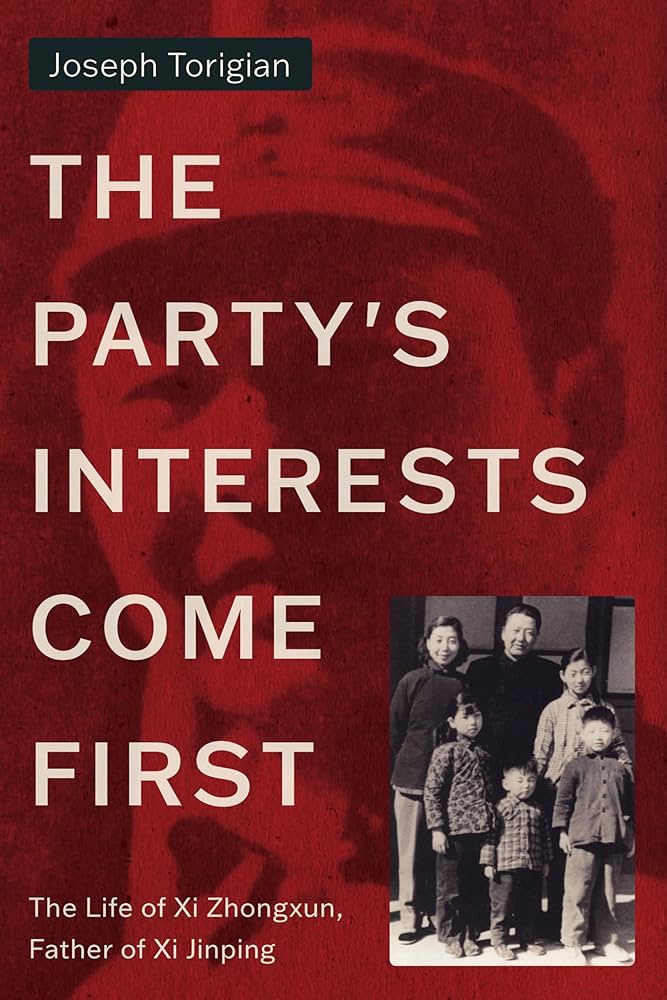

Today is publication day for The Party’s Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping, by Joseph Torigian. Those of us who occupy nerdy China circles have long been anticipating this book, which is a comprehensive examination of Xi Zhongxun’s life and his work in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). A lot of early readers have focused on what The Party’s Interests Come First can tell us about Xi Jinping—that is, they look to see what Xi Zhongxun taught his son during the latter’s youth and ascent in the Party-state system.

To be sure, Xi Jinping learned a lot from Xi Zhongxun, both directly and by observing his father’s life-long dedication to the CCP, even after Xi Senior suffered a political downfall in 1962 that would last 16 years. “The Party’s Interests Come First” could very well be the Xi family motto. (Indeed, Xi Zhongxun’s wife Qi Xin also modeled this dedication, spending little time with her four children while she lived and taught at the Central Party School in the 1950s and ’60s.) But I also think it’s important to read this book and consider Xi Zhongxun’s life on its own terms.

Xi committed his first revolutionary act at the age of only 14—he and a friend tried to poison one of their school’s administrators—and he remained a faithful Party member until his death at the age of 88 in 2002. Xi fought the Japanese and the Nationalists, served in numerous high-ranking government positions, was the right-hand man to both Zhou Enlai and Hu Yaobang, and managed relations with ethnic and religious minority groups in China. His purge came before the Cultural Revolution started and hinted at what was to come. Even if Xi Jinping were a nobody, Xi Zhongxun and his career would still more than warrant a close look as we continue to write the history of China and CCP politics in the 20th century.

As I read The Party’s Interests Come First, I noticed a few themes come up again and again in my notes, so I decided to organize this post around a discussion of those rather than write a traditional review. (There will be plenty of reviews; both scholars and journalists are justifiably lauding Torigian for his exhaustive research and incisive analysis.) What does this book teach us about Xi Zhongxun, and the Chinese Communist Party as a whole?

Xi Zhongxun was a survivor.

Xi escaped death a remarkable number of times during his early years as a revolutionary, including one occasion in 1935 when (he would later claim) he was on the verge of being buried alive by fellow Communists amid an intraparty conflict before the arrival of a Mao ex machina saved his life. Even if, as Torigian writes, Xi exaggerated that particular story, the fact that Xi made it through the Sino-Japanese War and then the Chinese Civil War was something of a miracle.

It is, however, Xi’s overall instincts for political survival that come through most clearly in The Party’s Interests Come First. In the 1950s, Xi survived the purges of his close colleagues Gao Gang and Peng Dehuai; in the 1980s, he held on to his position when General Secretary Hu Yaobang was forced to resign from his. Torigian describes Xi as “cautious,” and there were times, such as during the Great Leap Forward, when he apparently chose to remain silent rather than attempt to speak truth to power. The Party’s interests came first, yes, but let’s not overlook the role that self-preservation might have played.

Xi Zhongxun suffered terribly at the hands of the CCP.

His normally careful political calculations makes Xi’s 1962 fall from political grace even more notable, especially since it came about thanks to Xi acting against his better instincts and “reluctantly” approving the writing of a novel based on the life of his mentor, Liu Zhidan. Xi knew that the book would resurrect old debates about Party history in the Northwest and on multiple occasions he attempted to discourage author Li Jiantong from pursuing the project. Xi eventually gave in to peer pressure from his old Northwest compatriots, though, and with his approval of the book he provided Kang Sheng and Deng Xiaoping the opportunity to improve their own positions in the Party by taking down Xi Zhongxun. Mao Zedong, for reasons “lost to history,” supported the anti-Xi bloc, and “twenty thousand people were persecuted as part of the ‘Xi Zhongxun antiparty clique.’ At least two hundred were beaten to death, driven mad, or seriously injured.”

Initially, Xi’s political banishment sent him into detention at home, then to a secluded Beijing courtyard house, where he wrote self-criticisms and studied Marxist texts. In 1965, Mao ordered Xi removed from the capital; he was sent to a mining-tool factory in Henan Province, where he volunteered for work on the line and refused to accept other workers’ attempts to lighten his load. After the Cultural Revolution began, however, a group of Red Guards kidnapped Xi and subjected him to repeated public struggle sessions. Then, in 1967, the People’s Liberation Army took custody of Xi and imprisoned him while also enabling the struggle sessions to continue. Finally, in 1968, Zhou Enlai ordered that Xi be returned to Beijing, where he remained under investigation until 1975.

Xi Zhongxun’s purge fractured his family, affected his mental health, and kept him out of power until he received a position in Guangdong Province in 1978. All of his children suffered during the Cultural Revolution, and one daughter died by suicide. Yet these years did not diminish Xi Zhongxun’s belief in the Chinese Communist Party. As Torigian writes,

In the party, suffering meant “forging,” or strengthening one’s willpower and dedication. Undergoing such trials would signify true faith in the cause, and caring too much about oneself was a symptom of a bourgeois, individualistic privilege. […] When Xi was incarcerated during the Cultural Revolution, as he paced back and forth every day to maintain his health, he memorized Mao’s writings. When people complained about party policies, Xi often bragged about his hardships to delegitimize their grumblings. In the early 1990s, Xi even boasted to a Western historian that although Deng Xiaoping had suffered at the hands of the party on three occasions, he had been persecuted five times.

Rather than hold a grudge against the CCP for the trials he endured, Xi saw in them a higher purpose and a way to demonstrate his continuing commitment to the Party.

Xi could be flexible and pragmatic, but ultimately always upheld the rule of the CCP.

From his early days working with Liu Zhidan in the Northwest, Xi absorbed “a ‘big-tent’ philosophy when it came to revolution” and learned that, as he wrote later in life, “The more friends the better.” Xi wasn’t necessarily a sophisticated political thinker—his formal education ended when he was a teenager, and unlike many early CCP leaders he didn’t spend time studying with other revolutionaries in France or the Soviet Union. Instead, his belief in Communism was based on his experiences of peasant society and seeing the struggles most common people in China faced. If they wanted to join the revolution, Xi welcomed them.

This perspective set up Xi Zhongxun for his main focus as a CCP official: the United Front, “an influence campaign to co-opt other parties, prominent unaffiliated individuals, powerful ethnic-minority leaders, and the Chinese diaspora.” He had a long friendship with the 10th Panchen Lama and for years wore a watch gifted to him by the Dalai Lama. Xi could be charming and amiable, which positioned him as a natural interlocutor for the foreign visitors who came to China during the 1980s.

Such expansiveness would cast a shadow on Xi during those times when hard-liners reigned in the CCP and anyone who had contacts outside the Party became vulnerable to accusations of being an “accommodationist.” Yet Xi would never put the United Front above the Party. When Tibetan Buddhists began to protest in the late 1980s, “His immediate inclination was to tighten control, not double down on openness and give further space for religious activity.” Xi believed that CCP rule would improve life for everyone and demonstrate to United Front groups that supporting the Party was in their best interests.

We should use caution in calling Xi Zhongxun a “reformer.”

In the 1980s, Xi developed a reputation as one of the reformers in the CCP. He encouraged the growth of Special Economic Zones and endorsed a certain amount of flexibility on policy matters. He resumed his United Front work, seeking to improve the PRC’s relations with ethnic and religious minorities, and worked with reform-minded leaders like Hu Yaobang. He continues to be remembered as a cadre who worked to achieve a more liberal and humane CCP during that decade.

But how much of a “reformer” could a dyed-in-the-wool revolutionary and loyal Party man really be? Torigian explores the limits of Xi Zhongxun’s reform-mindedness, especially in his chapter on the 1989 protests and June Fourth massacre. Many interviewees told Torigian that they assumed Xi opposed Deng Xiaoping’s decision to use violence against the protesters—a point of view he regards as “tantalizing” but not backed up by available evidence. Xi’s personal thoughts on the crackdown remain unavailable to use, but we do know that in the end, Xi “supported the party after a decision was made, as he had done so many other times earlier in his life.”

Xi Zhongxun was scrupulous about living according to Communist ideals, except when it came to supporting Xi Jinping.

As a father, Xi Zhongxun had a reputation as “a ferocious disciplinarian” who sought to instill modesty, frugality, and dedication to the revolution in his children. His children might have been “princelings” due to their parents’ position in the Party, but Xi wanted to ensure that they would remain close to the people and remember why the revolution had been fought.

The one exception Xi Zhongxun made to upholding these principles concerned Xi Jinping. “Xi’s other children often complain in reminiscences that Zhongxun actively undercut their careers,” wanting to ensure that they would have to work for whatever they got. But he saw a special promise in Xi Jinping (once remarking that his son “has the makings of a premier!”) and sought to help advance Jinping’s career after his graduation from Tsinghua University in 1979.

Xi Zhongxun’s attempts at patronage didn’t always work, though, and “even individuals who sincerely respected Zhongxun believe that the nepotism he openly displayed toward Jinping was a rare black mark on Zhongxun’s storied career.” Xi Zhongxun retired in the early 1990s, a time when anti-princeling sentiment was also on the rise. Xi Jinping held positions throughout the decade, but his career was on the verge of stagnating at the time of his father’s death. Only after Xi Zhongxun’s passing in May 2002 did Xi Jinping get a major promotion, becoming Party Secretary of Zhejiang Province in November of that year and also securing election to the CCP Central Committee. Five years later, Xi Jinping ascended to the Politburo Standing Committee and locked in his status as heir apparent. Xi Zhongxun “did not live to see his son’s career take off,” Torigian writes, but Xi Jinping fulfilled the promise his father saw in him.

In 2001, Xi Zhongxun offered a concise assessment of his life: “I did justice for the party, did justice for the people, and did justice for myself; I did not make ‘leftist’ mistakes, I did not persecute people. My accomplishments have been ordinary. I feel no guilt.” As Torigian ably demonstrates, there was much more to Xi Zhongxun’s life—good, bad, and complicated—than those three sentences would indicate. The Party’s Interests Come First provides a fascinating study of one man’s life and legacy inside a political organization that often seemed to subsume individuals but was also constantly reshaped by their influence and the repercussions of their actions.

Featured photo: Xi Zhongxun greets the 10th Panchen Lama, 1951. Image via Wikimedia and in the public domain.

Leave a comment