A small exhibit of artwork by Burhan Doğançay (1929-2013) has just opened at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Art. “Post No Bills: Burhan Doğançay’s Archive of Urban Protest” includes several of Doğançay’s collages, which were inspired when he looked at a wall in New York while serving there as a Turkish diplomat in 1962. Adorned with weathered scraps of old posters and advertisements, Doğançay realized (as the exhibition introduction states) that the wall was like “a beautiful abstract painting composed by humans, nature, and time.” Although trained as an economist before he entered the foreign service, Doğançay had a long-standing interest in art (his father was a well-known painter), and this moment soon prompted a career change. He quit his job and began life as a photographer and artist.

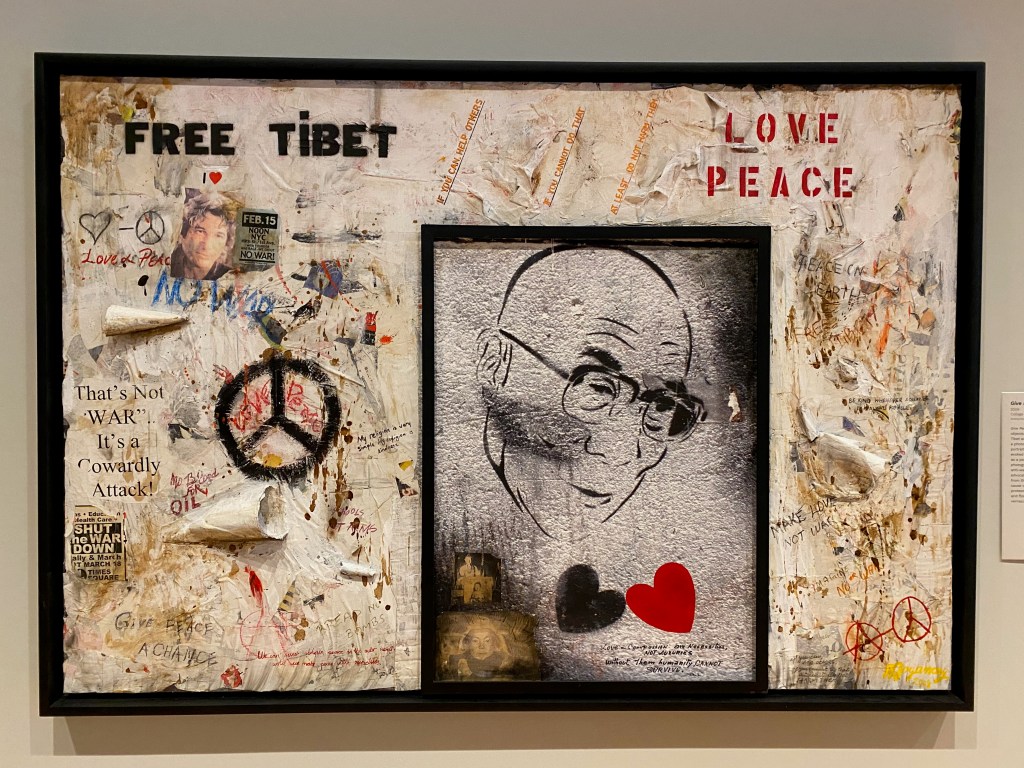

Curated by art historian Elizabeth Rauh, “Post No Bills” shows how Doğançay took that initial revelation and developed it into pieces that incorporated images and messages that he spotted on city walls around the world. Often using found materials, he built layers of paper and paint around different themes. Although Doğançay didn’t claim a political message for his work, it’s easy to imagine one when looking at a collage like Give Peace a Chance:

Attending a short introductory tour of “Post No Bills” made me think about walls and public spaces in a new way. Unauthorized posters, advertisements, graffiti—they’re usually regarded as a blight, something that needs to be removed and corrected. Doğançay’s artwork guides us to consider how those postings layer upon each other to express the dreams, anger, and objectives of various people at different points in time. What’s important? What are people railing against? What’s being sold, created, marketed, fought for at a given moment? The answers can be found by examining illicit postings and “the messy cacophony of these urban bulletin boards.”

I left the museum and walked toward my car, which I had parked across the street next to a column of campus postings. I rarely give these more than a glance, since they generally don’t pertain to me, but this time I thought to take a closer look.

Flyers for a church, advertisements for an improv comedy show. An upcoming presentation on “Should I Go To Law School?” Participants needed for a study on race and ethnicity courses at Michigan. Requests for donations to help a family in Gaza rebuild their lives. Posters for student housing. A rally against DTE, the local energy company.

Some of the papers were bright and fresh, while others showed signs of exposure to Michigan winter weather; below the recent additions, I could see layers of older postings whose messages were no longer visible, and maybe no longer timely. Ephemeral as they may be, someone like Burhan Doğançay could collect a pile of those flyers and turn them into a commentary on what’s going on and what concerns students at the University of Michigan in 2025.

The energy and layers of Doğançay’s collages demand careful study and re-engagement by the viewer; words and images seem to appear with each sweep of the eyes over the piece. And, I realized, these visual archives of the past also encourage viewers to look around and take notice of present-day postings—messages that perhaps aren’t directly relevant to them, but which help capture where we are and what we care about at this place and in this moment.

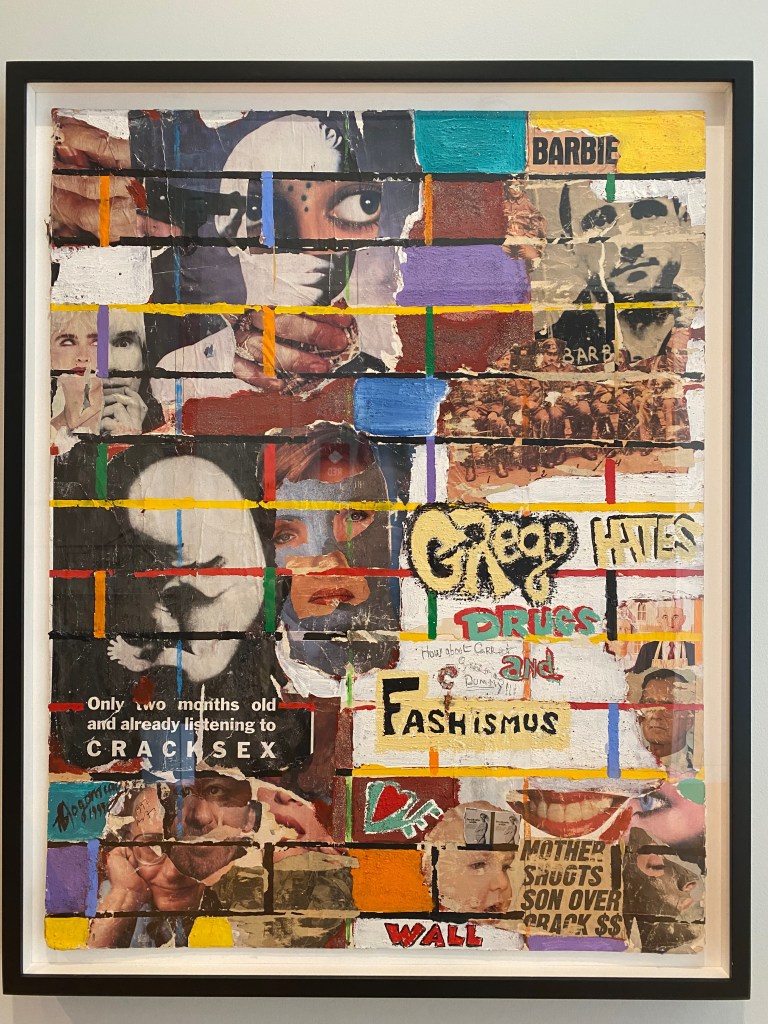

Featured photo: Carlos the Jackal, Burhan Doğançay, 2008, at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, March 2, 2025.

Leave a comment