Walk up the stairs to the “goblet” level of the National Monument in Jakarta’s Merdeka Square and you’ll enter the Hall of Independence. On a Sunday afternoon, the room is filled with people seated on all levels of the risers that ring the hall’s exterior. Adults chat or look at their phones, while kids dash up and down the wide platforms; the more daring youngsters scale the steep walls that angle sharply away from the top riser to meet the ceiling. Occasionally, a parent will bring their child over to the column in the middle of the room and stop before the ornate gold frame on one side. They point to the glass case within the frame and gesture at the single sheet of paper inside: the Proklamasi.

Indonesia’s declaration of independence is an unassuming typed page, two sentences and two signatures sufficient to set the country on a new course:

We the people of Indonesia hereby declare the independence of Indonesia. Matters concerning the transfer of power and other matters will be executed in an orderly manner and in the shortest possible time.

Below this brief memo, new president Sukarno and vice president Mohammad Hatta have scribbled their names, a pair of individuals speaking on behalf of millions of citizens spread across thousands of islands. On August 17, 1945, Sukarno stood before a slender microphone, Hatta several feet behind him, and read the text of the Proklamasi to a small audience gathered at his Jakarta home. Indonesia celebrates its independence every year on August 17, linking its status as a sovereign nation to the Proklamasi’s issuance.

On an immediate level, Sukarno and Hatta were assuming the reins of government from the recently defeated Japanese, who had occupied Indonesia as part of the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere since March 1942. But the Proklamasi’s true target was the Dutch government back in the Netherlands. This tiny kingdom perched at the edge of Western Europe had colonized Indonesia—the Dutch East Indies—for nearly 350 years, relentlessly extracting what it could while doing the bare minimum to benefit the people living under its rule. Sukarno, Hatta, and their compatriots in the anti-colonial movement that had emerged during the 20th century were determined to see Dutch control of Indonesia end.

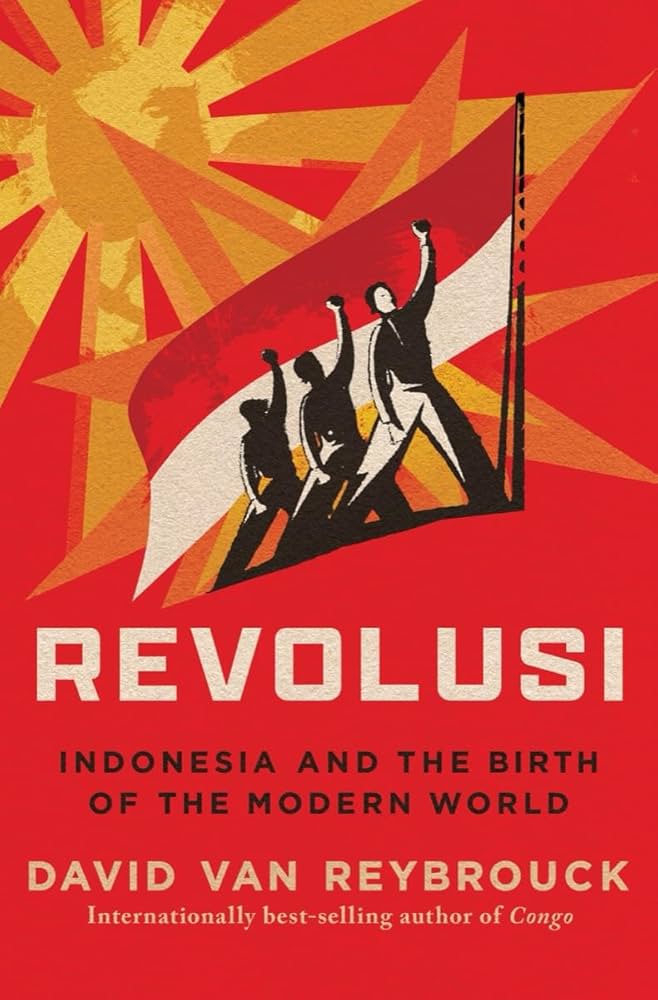

Historian and author David Van Reybrouck recounts the full story of Indonesia’s years under colonialism and the struggle to achieve independence in Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World, a magisterial work of non-fiction. Published in Dutch in 2020 and now available in English translation from W.W. Norton, Van Reybrouck’s book synthesizes a massive quantity of secondary literature and blends this narrative with accounts from 185 oral histories that he conducted between 2015 and 2019. Speaking with people from all sides, Van Reybrouck draws out in sometimes painful detail what it was like to live in Indonesia during the years of colonialism and the fight for freedom.

Van Reybrouck starts his story not with the Proklamasi (which is not promulgated until page 288, of 521) but at the very beginning, with the dawn of Dutch colonialism under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company in 1605. Indonesia wasn’t Indonesia then, nor was it the Dutch East Indies. “It’s helpful,” Van Reybrouck instructs, “to think of the island empire as a jigsaw puzzle put together over more than three centuries.” A panoply of autonomous kingdoms stretched across the archipelago’s islands; one by one, between 1605 and 1914, they fell to Dutch (or, for a brief period, British) control. The Europeans had first been lured there by the presence of spices—nutmeg, pepper, cloves—but stayed for the other agricultural products that the islands produced in abundance, including sugar, tobacco, coffee, tea, and cotton. Dutch plantations thrived on a supply of what economists would call “cheap labor,” a euphemism for exploited Indonesian workers.

Using the helpful metaphor of a steamship’s passenger classes—“colonial society in microcosm”—Van Reybrouck discusses socio-economic stratification and personal experiences of colonialism. In 1901, Queen Wilhelmina announced the “Ethical Policy,” which “called for more educational and economic opportunities, improved health care, more intensive missionary work and better infrastructure” to benefit Indonesians. What the queen didn’t anticipate was that those who were able to move up on the “colonial steamship” would find themselves continually frustrated by deep-seated legal and racial divides between the colonizers and colonized. The Ethical Policy, Van Reybrouck explains, “gave to the natives with one hand and kept them in place with the other.”

By the 1920s, young Indonesians who had received education but not equality from the Dutch began to form anti-colonial factions. The groups had different driving forces—political Islam, communism, and nationalism—but shared an insistence that they needed to be free of foreign rule. The desire to be rid of the “Dutch East Indies” moniker led to the adoption of “Indonesia” as the new appellation for the archipelago, which was now a fully assembled jigsaw puzzle of a country. National consciousness had formed among the activists. “No longer did they see their country as a section of the world map with fairly arbitrary borders,” Van Reybrouck writes, “but as a natural, unified nation with its own name and its own people.”

“Oil was the nutmeg of the twentieth century,” Van Reybrouck observes, and it was the need for oil that brought Japanese forces to Indonesian shores in early 1942. After centuries of Dutch misdeeds, many Indonesians welcomed the Japanese as liberators, and Sukarno attained national prominence thanks to the platform he gained from working with the occupiers. In Van Reybrouck’s account, Sukarno and others who might have been branded collaborators found a tidy mental work-around to justify their decision: “Strategic cooperation with the occupiers was a necessary part of moving forward with the national struggle, a form of opportunistic cooperation rather than ideological collaboration.”

The wartime years in Indonesia were brutal, marked by disease and hunger, violence and death, and these chapters of Revolusi are difficult to read. There’s no relief with Japan’s defeat, as the country almost immediately slid into the fight for independence—the Revolusi itself.

Van Reybrouck devotes the second half of the book to a detailed account of the Revolusi years between 1945 and 1949. He skillfully weaves together a mind-boggling tapestry of people and stories, which can become difficult to keep straight. This jumble of names and episodes stems, in part, from the fact that the Revolusi was not merely a vertical conflict between the Indonesians and the Dutch: the Americans and British got involved, too, as did a multitude of other countries via the newly created United Nations. Time and time again, the outsiders misjudged and underestimated the force of the Indonesian independence movement, failing to grasp the nature or intensity of grievances against the Dutch. They dismissed the Proklamasi, and the new government that Sukarno quickly established, as irrelevant, and were caught off-guard when efforts to reinstate Dutch control provoked large-scale opposition.

Sukarno, Hatta, and many other nationalist leaders had decades of experience working in the anti-colonial campaign. The driving force of the fight, however, was the pemuda, or youth. “The Revolusi,” Van Reybrouck observes, “was in every respect a youth revolution, supported and defended by a whole generation of fifteen- to twenty-five-year-olds who were willing to die for their freedom.” Their support for the cause did not necessarily have roots in nationalist ideology or the writings of intellectuals, but rather in the personal experiences of colonization that Van Reybrouck draws out of his interlocutors. “Over and over again,” he explains, “they had directly experienced the systemic mistrust, the far-reaching segregation and the everyday humiliation” of colonial rule. The Dutch, British, and Americans concerned themselves with the details of high politics, failing to absorb realities on the ground.

When the Dutch retook control of the archipelago in late 1946, they did so allegedly as partners with leaders of the new Indonesian government, the result of an agreement negotiated in the town of Linggajati. Even with the passion of the pemuda and public calls for a more aggressive move toward independence, the established Indonesian leaders were willing to work with the Dutch, so long as their side was treated with consideration and respect. By the middle of 1947, however, the whole fragile arrangement had collapsed and the Netherlands launched a military offensive. “It was the Dutch who had let themselves be whipped up to more and more unreasonable demands and increasingly hysterical ultimatums, despite the equality they had avowed so solemnly at Linggajati,” Van Reybrouck notes, and the conflict turned into an enormously expensive undertaking for a Dutch government that could little afford it after the devastation of the war years.

A brutal, no-holds-barred battle to win Indonesia ensued, and Van Reybrouck shares accounts of gruesome war crimes that remain unresolved to this day. In the Netherlands, the government has admitted to “excesses” and promised a full investigation, but the 1971 Limitation Law ensured that offenses committed in Indonesia would fall beyond the reach of prosecutors.

The fight ground on, now one of the many clashes between colonizer and colonized that emerged as the postwar world rearranged itself. “Colonial issues had become world politics,” and the United Nations, a new player on the scene, began to insert itself into what would have formerly been considered internal matters. Indonesia became a prominent item on the UN agenda, starting with a landmark resolution in August 1947 that called for a ceasefire between the Dutch and Indonesians—the first time the UN assumed jurisdiction over a conflict.

By early 1949, the Dutch cause was in tatters, its international standing weakened. The United States led other members of the UN Security Council in composing an even more forceful resolution that demanded an end to the fight and instructed the Dutch to transfer sovereignty of the country to local leaders by July 1950. Isolated on the international stage, the Dutch also found that any remaining support for them within Indonesia had also dissipated, its onetime allies turning away from the colonizers and joining forces with the pemuda. After making its final, and most deadly, military push throughout 1949, in August the Dutch government found itself in a conference room at The Hague negotiating a transfer of sovereignty with the Republic of Indonesia, represented by Hatta. Four long and savage years after Hatta watched Sukarno read the Proklamasi, he helped achieve the full realization of the document to which he had affixed his signature back in the first heady postwar days.

Indonesia, Van Reybrouck writes, is virtually invisible on the global stage today—a curious state for the country with the fourth-largest population (and largest Muslim community) and broadest island span (crossing three time zones), as well as an attractive tourist destination in Bali. Revolusi brings readers back to the time when events in Indonesia influenced anti-colonial fighters around the world. Indonesia’s fight for freedom

… shaped expectations about the nature of decolonisation: not a gradual, decades-long process of increasing autonomy, but a swift transition to independence. Not limited to one small portion of the colony, but affecting the entire territory. And not restricted to a few specific powers or ministries, but constituting a complete transfer of political sovereignty. Fast, comprehensive, and complete: that was the model forged in Indonesia and actively pursued in many other parts of the world in the decades that followed.

The Proklamasi alone did not achieve that “fast, comprehensive, and complete” state of independence. Indonesia’s anti-colonial leaders could not will their country into being; it took a hard-fought war to make it a reality. Nor would those four years of fighting mark an end to conflict: in a brief final chapter, Van Reybrouck goes into the post-independence history of Indonesia and the role the United States played in enacting regime change when Sukarno fell in 1965, which resulted in horrific violence and the deaths of up to a million Indonesians.

In Revolusi, Van Reybrouck always comes back to the accounts of people who experienced the years of Dutch rule, Japanese occupation, and the fight for Indonesian independence firsthand. Like the “jigsaw puzzle” of Indonesia itself, these stories fit together to create a fascinating, if deeply troubling, historical picture—one that is often, inexplicably, overlooked by those outside the country. Revolusi vividly conveys that Indonesian independence might have started with a two-sentence proclamation, but it was achieved through the support and sacrifice of people all across the archipelago.

Featured photo: Diorama of Sukarno reading the Proklamasi, Indonesian National History Museum, July 7, 2024.

Leave a comment